Featured image: Allie Caulfield via Creative Commons

In the summer of 1933, Mark Rothko, who was then still known as Markus Rothkowitz, hitchhiked nearly three thousand miles from New York City to his hometown of Portland, Oregon. He had done this several times in recent years, having moved east in 1921 to attend Yale University before withdrawing and settling in New York in 1923.

But 1933 was different for two reasons. First, he was accompanied by his wife, Edith Sachar. They had married the previous November, and the ostensible purpose of the trip was to introduce Edith to Rothko’s mother. Second, Rothko had his first solo exhibition, at the Museum of Art, Portland, in July and August. So the trip marked both a personal and a professional milestone for the aspiring artist.

Rothko’s Portland relatives were unable to host the newlyweds, so they set up camp in the hills overlooking the city. According to Rothko’s brother Moise (later known as Maurice Roth), “with canvas or whatever they had, they built themselves a hut there and lived with no facilities of any kind.” Canvas was suitable for a tent in the woods, but for painting outdoors Rothko favored paper. Lightweight and portable, paper was a logical choice for a peripatetic summer.

Neither a catalog nor a checklist has been found for the Portland exhibition, but Catherine Jones’s review in the local newspaper described the works on view as watercolors, “chiefly landscapes,” that revealed “a hint of his admiration of Cézanne,” as well as works painted with “black show card or poster paint” on “the sheets from a 10-cent tablet of linen writing paper.”

Untitled (seated woman in striped blouse), 1933/1934, watercolor on construction paper, 11 × 8 13/16 in. (27.9 × 22.4 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.56.472.

Untitled (seated woman in striped blouse), 1933/1934, watercolor on construction paper, 11 × 8 13/16 in. (27.9 × 22.4 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.56.472.

Rothko’s landscapes were received positively. “The artist has sought to retain the effect of complexity one finds in the out-of-doors and to show its ultimate order and beauty,” Jones commented, continuing, “They are carefully thought out and in no way theatrical or dramatic.” Untitled (Portland, Oregon), a view of the Willamette River and the valley beyond, places the artist in Forest Park in the Tualatin Mountains west of downtown Portland. Mount Hood is hinted at in the cloudlike peak at the upper edge of the sheet.

Rothko produced numerous watercolors from this vantage point, possibly Terwilliger Boulevard, a scenic parkway that winds along the hills near Forest Park. These works demonstrate Rothko’s familiarity with landscape painting conventions, with large trees framing a view that often features a body of water. Forest interiors also likely date from that summer. Semitranslucent watercolor paint applied with staccato hatching or jostling parallel strokes, pooled transparent washes, and reserves of textured watercolor paper produce sparkling atmospheric effects. An early interest in abstraction is evident, too, as foliage and tree trunks verge on pure gesture and patterned latticework.

The elevated vantage point and the clean palette of Rothko’s early landscape watercolors suggest something of the elation and confidence the artist may have been feeling. At twenty-nine years of age, Rothko was married and, with a first solo museum show to his name, could arguably declare himself to be a professional artist. Rothko’s lively watercolors give the impression of an optimistic beginning to a bright career. Jones thought as much, noting that Rothko had “reached the one-man show stage in a career that promises to be highly successful.”

Promise, though, does not pay the rent. Rothko was struggling financially. He was expected to help support his family, but it was the middle of the Great Depression. His employment in recent years had consisted of a variety of part-time jobs. He worked as a cutter and bookkeeper in the Garment District, in advertising, and teaching art to children. Rothko was also trying, unsuccessfully for the most part, to sell works like those in the Portland exhibition.

Rothko walked a fine line between experimental risk and studied control.In the absence of sales, he gave numerous Portland watercolors as gifts to his relatives. A cousin, surely exaggerating, recalled years later that Rothko’s mother’s closet was filled with “hundreds” of them. Rothko had attended Yale intending to become an engineer or a lawyer, and his family did not fully understand his decision to pursue art.

Handing out paintings was a gesture that reinforced his career choice and identity as an artist to his skeptical family. It may also have been an act of wishful thinking—sharing as aspirational advertising. He offered early works to friends and acquaintances in appreciation for special treatment or services that he could not otherwise afford.

In Portland in 1933 Rothko also played the role of curator, overseeing a display of works by his young students—aged five to fourteen—from the Center Academy of the Brooklyn Jewish Center, where he had been teaching part-time since 1929 and would continue to do so until 1946. Rothko admired his students’ work and shared their approach and materials, as in a remarkable body of vibrant figural watercolors painted on colored construction paper, a cheap pulp paper produced and marketed primarily for children’s use. A half-length portrait of an intensely focused woman in a striped, orange blouse features the saturated color, swirling, and bleeding Rothko was able to conjure from these humble materials.

The Bathers, 1934, watercolor on construction paper, 12 1/4 × 15 in. (31.1 × 38.1 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.43.198. Inventory number 1075.25–27.

The Bathers, 1934, watercolor on construction paper, 12 1/4 × 15 in. (31.1 × 38.1 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.43.198. Inventory number 1075.25–27.

Rothko painted loosely, wet alongside wet, to tease feathery edges from barely touching pools of paint. He also adjusted the ratio of dry pigment and water to create unusual, crinkled textures. Colored sheets of construction paper provided a toned background field that set the color palette and harmonies for the work. Rothko walked a fine line between experimental risk and studied control.

Sometimes he embraced the chance outcomes that arose when working with liquid media on paper; sometimes he carefully controlled the interaction of adjacent paints to prevent undesirable mixing. The surprising results display Rothko’s keen interest in the touch along borders of intense liquid color, the juxtaposition of matte and glossy surfaces, and scrims and stains enlivened by thicker strokes, as around the collar of the woman’s orange blouse. One cannot help but see in such watercolors the hallmarks of the abstractions to come more than a decade hence.

In his 1947 essay “The Romantics Were Prompted,” Rothko wrote that, for him, “the great achievements of the centuries in which the artist accepted the probable and familiar as his subjects were the pictures of the single human figure—alone in a moment of utter immobility.” He would likely have been thinking of seventeenth-century Dutch portraits—the psychological complexity of Rembrandt van Rijn or the absorption of Johannes Vermeer’s figures. It would seem that in these early construction paper watercolors, Rothko was trying to produce his own expressions of character and interiority.

A group of early 1930s portraits, quite possibly all of Rothko’s wife, Edith, display an almost confrontational directness, engrossed concentration, or melancholic distraction. Often one senses that Rothko struggled with individuals and the convincing portrayal of a genuine personality, reducing faces to blank masks. He seems freer and more confident in the backgrounds, the surrounding spaces, or the patterned surfaces of interior furnishings.

Untitled (seated figure in interior), c. 1938, watercolor on construction paper, 10 1/4 × 12 1/8 in. (26 × 30.8 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.56.511.

Untitled (seated figure in interior), c. 1938, watercolor on construction paper, 10 1/4 × 12 1/8 in. (26 × 30.8 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.56.511.

Rothko painted on construction paper at least 150 times in the 1930s. Many appear to be sketches, technical exercises, or exploratory studies, and some are related to known canvases. Others are highly finished, testifying to a serious level of attention and commitment. Several are inscribed with titles and prices and were once matted by Rothko himself, indicating that they may have been exhibited or offered for sale. Rothko frequently treated a composition multiple times on paper, revising and bringing the subject to a higher degree of finish.

Occasionally the work done on paper manifested on a canvas. And sometimes related works on paper and canvas were both public. In at least one instance, a composition treated in a closely related pair of works—one on paper and one on canvas—appears to have stimulated further exploration of the subject. Rothko painted a reclining woman in watercolor that he developed on canvas in a manner that clarifies the composition and lends her anatomy a convincing plasticity even as it flattens the perspective. A second watercolor then dislocates this nude altogether from a believable interior space, propping her almost upright against a patchwork pattern of golden browns.

Construction paper was recommended to Rothko by Milton Avery, whom Rothko and his contemporary Adolph Gottlieb had befriended in the late 1920s. The trio formed a close and long-lasting relationship, even gathering for weekly drawing classes in the early to mid-1930s. Rothko’s use of a nonmimetic palette for expressive ends in his figurative construction paper works was also likely prompted by Avery’s burgeoning exploration of vivid color.

In the summer of 1934, Rothko and Edith vacationed in Gloucester, Massachusetts, with Milton and Sally Avery and Adolph and Esther Gottlieb, having a “good, nice, wholesome time” on the beach during the days and spending evenings “talking about painting” or assembling impromptu sketch classes. Gottlieb recalled that he and Avery would “go out and make sketches of Gloucester Harbor or people on the beach… and then go home and paint them.”

For Rothko the result of this summer vacation was a series of watercolors of bathers. Several are signed and appear to have been exhibited. With high horizons and statuesque anatomies, Rothko’s beach scenes mimic Avery’s, which included, in at least one instance, Rothko himself wearing white and a visor.

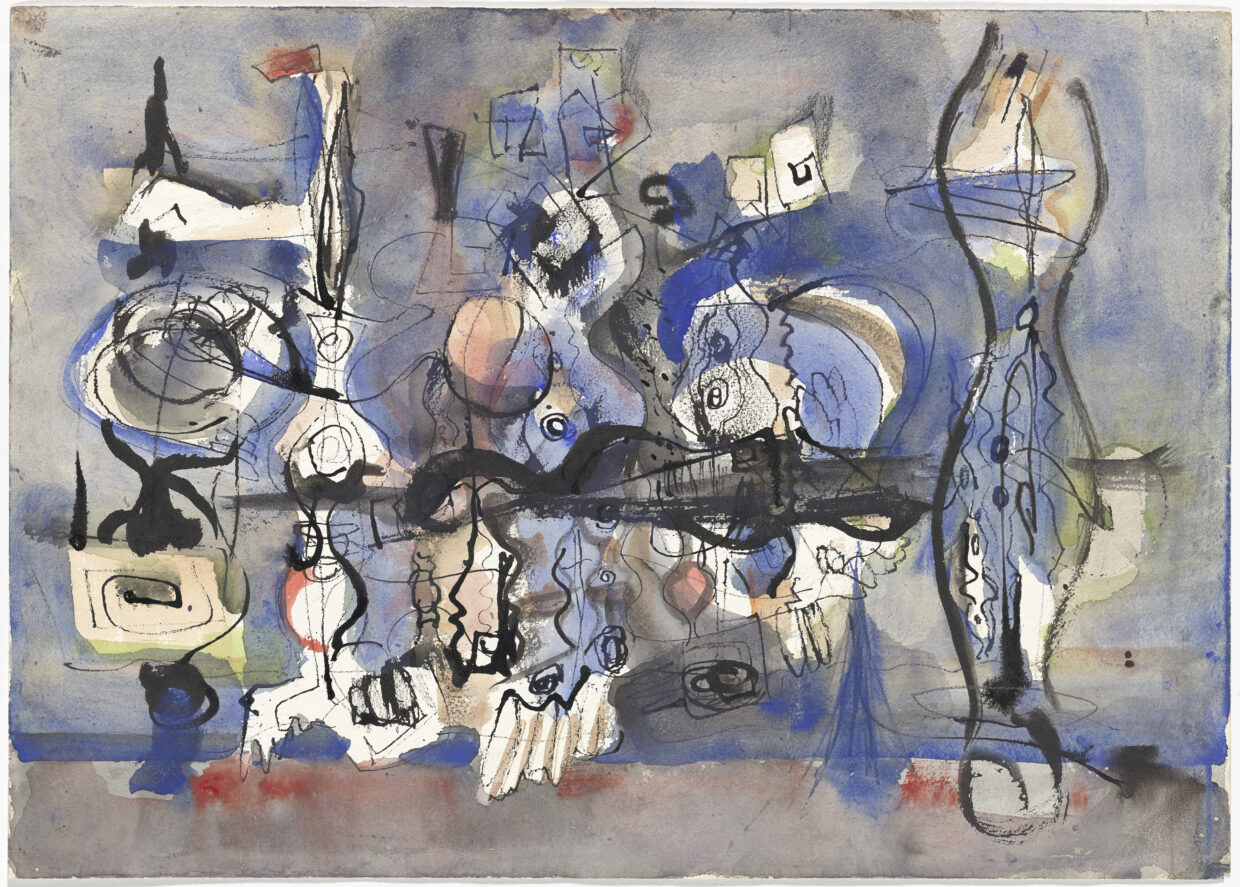

Untitled, c. 1944, watercolor, ink, and graphite on watercolor paper, 15 × 21 in. (38.1 × 53.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.43.178. Inventory number 1033.41.

Untitled, c. 1944, watercolor, ink, and graphite on watercolor paper, 15 × 21 in. (38.1 × 53.3 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of The Mark Rothko Foundation, Inc., 1986.43.178. Inventory number 1033.41.

Even though he had an obvious facility with watercolor, Rothko initially struggled to find a reliable market for these works. Edith remembered that he had taken early watercolors “to some of the galleries and he hadn’t gotten any reaction. Nobody wanted to show them. I don’t think they were presented very well. He didn’t frame them, he didn’t have the money, you know, to set them up. And some of them I think were very good. And I think he was disappointed. He had great faith in his watercolors.”

In November 1933, just after Rothko and Edith had hitchhiked back from Portland, he had his first solo exhibition in New York at the Contemporary Arts gallery. The show included oil paintings on canvas and watercolors. The latter received the most attention. The New York Times reviewer noted that the “water-colors and wash drawings are freest and most successful” and praised Flying Bridges for its “lightness and a graceful quality.”

The New York Sun reviewer, who described the artist’s style as “peculiarly suggestive,” wrote that Rothko’s technique was “better adapted to landscape, and to landscape in water color at that,” noting that “several water colors… really score, particularly Mount Hood, Portland, and Flying Bridges.” Margaret Breuning of the New York Evening Post praised one of Rothko’s canvases but noted that on canvas “the pigment is dry and brittle.”

Despite the positive responses to his works on paper and the fact that his intuitive, fluid, and expressive handling of water-based paints seems not to have translated to canvas, Rothko maintained, perhaps aspirationally, that he preferred painting in oils. He surely saw oil painting as the goal, given its long-standing hierarchical superiority to watercolor and his admiration of and desire to emulate artists like Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, and Rembrandt, whom he would have known for their paintings on canvas.

Perhaps encouraged by the modest attention garnered in 1933 by his works on paper, Rothko shifted his attention to canvas. He would make hundreds of drawings, sketches, and small preparatory studies in ink and graphite on paper in the mid- to late 1930s and early 1940s, but he would not exhibit any works on paper for the next decade, choosing instead to restrict his public-facing output to paintings on canvas.

__________________________________

From Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper by Adam Greenhalgh. Published by the National Gallery of Art, Washington in association with Yale University Press in November 2023. Reproduced by permission.

__________________________________

Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper is on view now at the National Gallery, Washington DC.