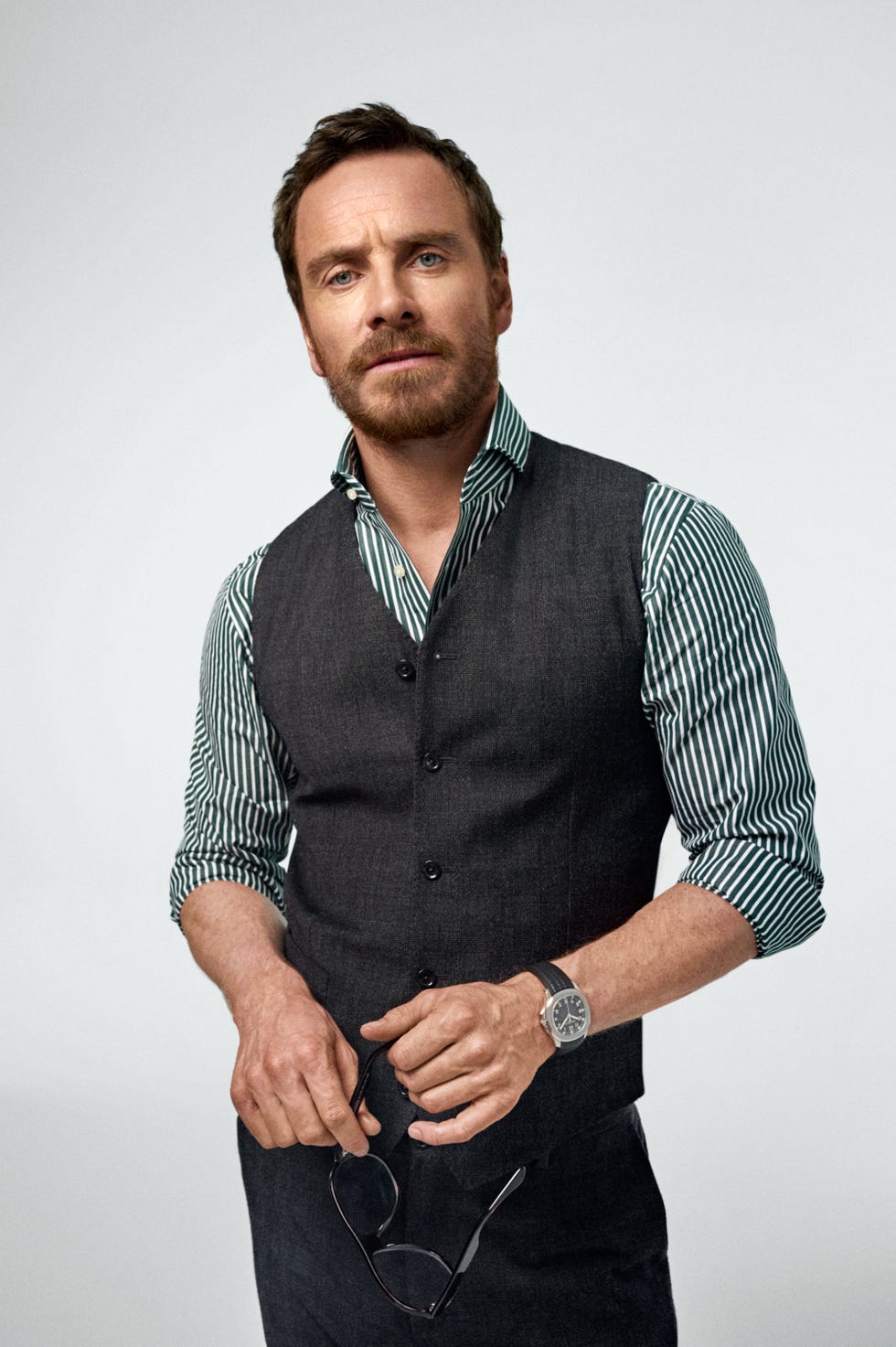

Fishing was his idea. To browse through Michael Fassbender's press clippings is to witness a man intent on transforming a burdensome professional obligation—parsing the ecstasies and devastations of his life for the benefit of strangers who write for magazines—into something fun and, on occasion, thrilling. He once coaxed a reporter into skeet-shooting in New Jersey. He went race-car driving in Montreal with another. Today, on an overcast autumn morning in Toronto, he wanted to be Captain Ahab.

Such activity planning doesn't stem from an aversion to discussing his craft. As far as theatrical pedigrees go, Fassbender's is unimpeachable—he's been nominated for two Academy Awards, he's played both Macbeth and Steve Jobs, and now he gracefully hops between challenging independent films and tentpole franchises like X-Men—and he is happy to pull back the curtain on his process. No, he goes on wild adventures to avoid talking about his offscreen life. It's as if he's flummoxed by the notion that there might be something compelling about it. During our time together, Fassbender would prove unquestionably polite, even kind, but also thoroughly uninterested in turning his personal life into a public narrative.

I could tell that Fassbender had arrived in the lobby of the Toronto Ritz-Carlton even before I saw him—the air got kinetic as guests and bellhops collectively, if not surreptitiously, refocused their attention on him. He was in town to premiere the crime drama Trespass Against Us at the Toronto International Film Festival, but I got the sense that he was already eager to escape the hubbub—all the glad-handing and awkward posing and great-to-see-you-agains, chirped at a high pitch by an endless stream of agents, studio execs, and moonily grinning admirers. So the two of us quickly made our way to the hotel restaurant and, over a shared stack of pancakes, reviewed our escape plan: We'd take a car to a wharf thirty minutes outside of town; meet our guide, a young fishing-boat captain named Aaron; and spend the day stalking rainbow trout and Chinook salmon in Lake Ontario. Fassbender was excited to be stepping away from civilization for a few hours, his voice now betraying a hint of an Irish brogue. "I don't even care if we catch any fish!" he admitted.

In an industry where the window for celebrity usually slams shut the moment a star's face is creased by a wrinkle, thirty-nine-year-old Fassbender is an anomaly: His career didn't take off until 2009, when he starred in Steve McQueen's feature-length debut, Hunger, as IRA prisoner Bobby Sands. Fame clearly still makes him uneasy—he became visibly uncomfortable whenever a server needlessly hovered or spent a few too many beats explaining the specials. He kept his head down each time we were outside. He darted nervously around every public space we passed through, ducking behind potted plants and other large objects like a kid playing hide-and-seek.

The unbidden attention continued after breakfast. As we half-jogged the twenty-five yards from the lobby to our idling car, a scrum of photographers scampered up, yelling his name. He was gracious but firm—maybe later, dudes! The exchange tipped off our driver, who later searched "Michael Fassbender" on his phone, which was mounted on the windshield at such an angle that its screen was clearly visible from the backseat. "Look, he's Googling me already," Fassbender said to me quietly, calling him out. "This is how it goes now."

Still uncertain of the magnitude of his cargo, our driver laughed nervously, smiled half-apologetically in the rearview mirror, and pulled out onto the road.

In The Compleat Angler: Or, The Contemplative Man's Recreation, a peculiar but amiable fishing manual published in 1653, Izaak Walton savors the ferocity with which salmon forge a path into freshwater when it's time to spawn—how desperately they work to repossess "the pleasures that they have formerly found" in the cold lakes and streams where they were born. To get home, the fish fling themselves to extraordinary heights—up twelve-foot waterfalls sometimes—by positioning their bodies in the current so as to turn themselves into a kind of self-loading slingshot. ("They beat the shit out of themselves" is how Captain Aaron later described it.)

Although many of us move through life this way—wandering off only to return to what we know best, which is often what we knew first—for Fassbender, the past is infinitely less interesting than the future. This winter's Assassin's Creed, which he both stars in and produced, is based loosely on the wildly popular video-game series—more than a hundred million units sold!—of the same name. It's the type of intense, eye-widening, era-spanning epic that can either bomb at the box office and decimate the movie studio's bottom line or sell a gazillion tickets and turn its steely-eyed lead into a coveted A-lister.

Fassbender plays two different characters: the present-day Callum Lynch and his fifteenth-century ancestor, Aguilar. Callum, who lost his entire family at an early age, is, for better or worse, exactly the sort of tragic hero—a young man with no family who is forced to go on a quest for self-realization—you'd expect to find in a film based on a game marketed chiefly to young men. He is, however, in many ways a curious choice for Fassbender, and not just because video-game movies are famously risky ventures. (Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and Warcraft, two big-budget reimaginings, failed spectacularly at the U. S. box office.) For most of his career, he's resisted playing characters a viewer can comfortably root for. Instead, more than almost any other living actor, he has chosen to make plainly depraved figures human—knowable, if not familiar.

In 2013's 12 Years a Slave, his third collaboration with McQueen, Fassbender was cast as Edwin Epps, a Southern plantation owner who falls in love with one of his slaves and rapes her; he plays Epps as a man who simply does not seem to understand the horror of his own life. (The performance earned him his first Oscar nomination.) Meanwhile, the central thematic conflict of last year's Steve Jobs was the Apple cofounder's repeated disavowal of his daughter despite clear genetic evidence of paternity. Jobs's position was objectively unsympathetic, but Fassbender still exhibited a disorienting self-possession onscreen, as if to suggest that maybe, somehow, he had more information than we did.

In conversation, Fassbender expresses a guileless hunger for new information. "I heard recently that the word hillbilly comes from followers of William of Orange— the men who lived in the hills. I love finding out stuff like that," he told me excitedly. We were waiting lakeside for our vessel to arrive. "Also, I didn't know that the word Cajun comes from Acadian. That's pretty cool, too!"

Fassbender started acting relatively late. He was born in Heidelberg, West Germany, in 1977, to a German father and an Irish mother. When Fassbender was two, his family relocated to southwest Ireland, where his father worked as a chef in the restaurant of a small country inn near Killarney National Park. He became interested in acting after enjoying a theater workshop. Although he was rejected by two acting programs he applied to, he got into the Drama Centre London. Shortly thereafter, he dropped out of school to pursue gigs more seriously; he scored a few commercials (in one popular Guinness ad, he swims across the Atlantic Ocean to resolve a quarrel with his brother) and a handful of supporting roles, including that of a sinewy, long-haired Spartan in 300. But it wasn't until McQueen cast him in Hunger that he found his footing. The film recounts Sands's gruesome sixty-six-day hunger strike in a Northern Irish prison. To convincingly embody the character, Fassbender lost about forty pounds by surviving on just six hundred calories a day. Hunger won the Caméra d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, and Fassbender was named Best Actor at the British Independent Film Awards.

Since then, the Fassbender thing—some unlikely mélange of vulnerability and fortitude; the way those winsome blue eyes seem to reflect both the misery and the joy of being alive—has attracted a murderers' row of auteur directors, including McQueen, Danny Boyle, Quentin Tarantino, David Cronenberg, Derek Cianfrance, Cary Joji Fukunaga, and Ridley Scott.

"His signature is playing these characters who have this incredible conflict inside them," Cianfrance, who directed Fassbender in this past summer's The Light Between Oceans, told me. He recalled first seeing Fassbender in Hunger: "I couldn't take my eyes off of him. He felt like a panther up onscreen," he said. "There's a translucency in his being; you look at him and you see exactly what's going on underneath, yet he doesn't betray a thing on the outside."

In Shame, Fassbender's second collaboration with McQueen, his portrayal of an otherwise-high-functioning New Yorker struggling with sex addiction feels pathological, fevered; in Fish Tank, a 2010 indie directed by Andrea Arnold, he plays a married man who seduces the wounded fifteen-year-old daughter of the woman he's dating on the side. In both roles, there's more desperation in his performance than depravity.

Even in a movie as emotionally uncomplicated as X-Men: First Class—in which Fassbender delivers some fairly preposterous lines of dialogue—he handles his role with uncommon tenderness. Toward the end of the film, when his former Nazi captor, Kevin Bacon's Sebastian Shaw, has been frozen in place via telepathic intervention, Fassbender's Magneto gently tilts his face toward Shaw's open palm, as if to say, "You knew me once." Then he kills him by slowly shooting a silver coin through his brain. The face-tilt is a tiny thing, and narratively inconsequential. It is also one of the most touching moments in any superhero film.

Fassbender is careful, even now, when describing the difficult men he's inhabited. I wondered if he thought these wounded, flailing people might be able to tell us something important about how hard it is to be a person, to hurt and to be hurt, and to try to stop one from being a catalyst for the other. "That's exactly right," he said, looking directly into my eyes. "Show me a straightforward path in life. It can be very simple, but it can get very complicated."

"I don't think Michael gives a fuck about 'taking risks,'" Kate Winslet, his costar in Steve Jobs, explained to me. "It's not in his nature to say, 'How far can I push this envelope?' He just wants to play characters that he knows will challenge him." In Fassbender's hands, even Steve Jobs—as inscrutable a visionary as we've ever had in America—becomes relatable, real. "Of course I'm paying your tuition," Jobs tells his Harvard-bound daughter in a late but pivotal moment in the movie. "I am not as terrible as you think I am" is the subtext of the scene. It might as well be the maxim for most of the characters he plays.

"I always liked him," Fassbender said, referring to Jobs. "I never wanted to represent him in a vile way. When I watch [the film] now, I just see someone who found it difficult to come to terms with other people."

Of course, the underlying lesson in these films is that true self-awareness is rare. It would have been far easier for Fassbender to give people what they want—to reinforce what we all believe to be true about wickedness, which is that we'll know it when we see it. But most people don't actually know how or why they are failing others. We're solipsistic creatures, willfully unaware of how badly we can behave toward those we care about.

Our boat was a thirty-foot Sea Ray, equipped with all the latest fish-hunting gear—sonar and depth sensors and dozens of top-of-the-line rods and lures. Fassbender immediately climbed on deck, and then helped me aboard. As Captain Aaron motored us off, Fassbender and I sat side by side, watching the Toronto skyline disappear. He leaned his face toward mine. "Do you think you could swim back right now if you had to?" he asked in a tone I'd describe as nearly cheerful.

Changing subjects, I asked him if he was a serious gamer—if he'd come to his latest project as a fan. "The last time I had a serious stint with video games was 2000," he said. It was a year before he got his first significant part, a small role in the World War II miniseries Band of Brothers. "There was a period of time where I was working in this warehouse at night. I would come home in the morning and just sit down in front of this racing game—I can't remember the name of it—and play it over and over."

Anyone who has engaged in any kind of day-erasing activity knows what it means to find a way to blur the edges just a little—to make the drudgery of life less palpable, if only for a brief period of time. He spoke about tedium and oblivion with a hint of wistfulness—as if tapping into the lives most of us lead were essential to him but becoming less attainable by the day.

As we moved farther from shore, he showed me photos on his phone from a few weeks earlier, when he was casting for mackerel with his dad in Ireland. The vistas were breathtaking—craggy mountains and a sky so vast and vibrant that it looked like desktop wallpaper. "Look at that," Fassbender said with palpable pride in his voice. "It's incredible." He paused and thumbed through some more shots, stopping on one of him and his father; he was wrestling a bent rod. "Here's me, bringing that sucker in!"

Although Fassbender routinely seeks out experiences that involve solitude—he loves to surf and he still lives in London, thousands of miles from Hollywood—he doesn't consider himself a loner. What he likes, he said, is collaboration—people sharing ideas in the service of something bigger, something beautiful. "The prep—spending hours and hours by myself, reading and rereading the script—I find that to be the tough part."

Twenty minutes later and about seven miles offshore, we dropped anchor. Fassbender chatted amiably with Captain Aaron, inquiring about the various rods onboard and the different strategies for baiting them. We cast our lines.

Fishing is the sort of activity—like sex or skateboarding—that's only fun once you're good at it. Despite our previous angling experiences—I've fly-fished some; he tries to get out on the water whenever he can—we were not having much success. As we stared at our unmoving poles, we discussed our past triumphs. We'd both run track growing up—for him, the one-hundred-meter and two-hundred-meter sprints, some hurdles. He wasn't an impish underdog, but he never broke through as a top-tier athlete. Perhaps he was being unnecessarily humble; he also severely downplayed his acting skills, maintaining that anyone could do what he does, provided they were paired with a competent director. (All it takes is an afternoon at the movies to see that this is plainly untrue.)

The spirit of the day was Canadian-nice, as we politely shared bottled water and pleasantries. Our eyes stayed on the lake. Captain Aaron insisted that the cloudy weather was fine, even favorable, for salmon fishing. He had the dadlike comportment of a man who was constantly being forced to answer unanswerable questions about the proclivities of fish. We'd catch salmon, he assured us.

Then, suddenly, one of the lures we'd tossed out was live. Captain Aaron shot up. "Ladies first," Fassbender said, stepping aside. I grabbed the pole, jamming its butt against my hip, and started furiously reeling in my line. "I think it's just a little one," Captain Aaron offered at least three times, tempering expectations. On the hook was, indeed, a tiny Chinook salmon, probably only a year old. I did what anyone would do when they've just caught a fish with Michael Fassbender—I handed him my phone and posed for a photograph with the fish ("Yeaaaaaaah!" he yelled)—and then Captain Aaron helped me unhook it and toss it back.

The glory was short-lived. A few minutes later, not long after losing what appeared to be a genuinely enormous rainbow trout—it leaped out of the water and off his line, a lone beam of sunlight illuminating the lovely pinkish stripe on its side—Fassbender hooked a salmon. Captain Aaron ran for a net to help him pull it onto the boat. Fassbender freed it and grinned. It was big.

It's hard to recall whose idea the footrace was. But there we were, back on land after our two-hour fishing trip, crouched three in a row, eyeing a stretch of lumpy parking-lot blacktop: me, Fassbender, and Captain Aaron. We'd set ourselves up to charge maybe fifty meters toward a yellow barrier separating the marina from the lake. I'd been tasked with counting off the start. Fassbender emptied his pockets, tossed his cell phone on the grass. He stretched. Captain Aaron was wearing what appeared to be actual running shoes. I was dropping lines like "Oh, yeah?" to no one in particular.

I counted down. We ran. Fassbender won by a wide margin.

The man loves music. Earlier that morning, he'd asked me about my favorite bands. When I'd mentioned I'd been listening to the Misfits, the late-seventies punk band once fronted by Glenn Danzig, he'd said, "Oh-kay!"—like, Here we go!

Later in the day, he launched into a story about a band he was in during high school, though he quickly clarified that calling it a band was an overstatement: two guys, two guitars. They played just one gig, in a restaurant, and were asked to turn their amps down until they were essentially playing Metallica songs on unplugged electric guitars.

On the drive back to the city, he told me about the time he saw Nirvana in Dublin in 1992—the Nevermind tour, with the Breeders opening. He was fifteen. "It was a bad gig, though. They weren't into it," he said. On the subject of the speed-metal band Slayer, he murmured, "Reign in Blood," the title of their best album, as if presenting a statement of fact.

He was clearly enjoying this—his lungs full of fresh air, the conversation focused on musicians as windows into our younger selves. He got quieter as we neared the city. Over a post-fishing, post-race lunch—greasy Cuban sandwiches—a woman directly across from us started waving her phone around in the air, as if this were still how a person managed to acquire a cell signal.

He stopped midsentence to take note. "She's filming me right now and pretending that she's not." I looked over, but the woman avoided eye contact.

Fassbender was loath to grumble about the unrelenting invasiveness of fame, both this morning and now, but it was easy to see that it exhausted him. "It's kind of creepy—people know where you're sleeping and shit," he said with a sigh.

I tossed off a question about how challenging it must be to be one half of a famous couple—he has been dating his Light Between Oceans costar, Swedish actress Alicia Vikander, since late 2014—but he assured me it is in fact very simple, because they have chosen not to talk about their partnership. They're each willing to acknowledge that the relationship exists and to repeat kind and respectful platitudes about how hardworking and inspiring the other is. But neither is willing to betray anything intimate. It is hard to argue with the logic of having a self-protective approach toward people he loves.

Fassbender is close to his family—his parents, who still live in Ireland, and his sister, who's in California. "They're very much a part of who I am," he told me. "Somebody was asking me last night, when I do emotional scenes, how do I go about getting there? What I do more often than not is pray to relatives who are gone. I feel like they are there with me. There are times in life where I've just thought, Somebody was looking after me there. Somebody was looking out for me." He laughed at the corniness of it all, but I could tell the idea was important to him.

After we finished lunch and hugged goodbye—Fassbender skittered out of the restaurant, stopping only to shake a couple hands—I remembered something he'd said on the boat.

I'd been grumbling about how difficult it was not to try to reason through an activity like fishing, which by its very nature is unpredictable. This was probably also true of living, I'd joked. "It's true of everything!" Fassbender had said. "You do it the first time, and then you overthink it. There's too much thinking in life."