Junk history is embodied perfectly in a recent viral meme that portrays a nineteenth-century Persian princess with facial hair alongside the claim that 13 men killed themselves over their unrequited love for her. While it fails miserably at historical accuracy, the meme succeeds at demonstrating how easily viral clickbait obscures and overshadows rich and meaningful stories from the past.

By Victoria Martínez

Not everybody has been convinced over the “Princess Qajar” meme, which claims that this Persian princess with an apparent mustache was considered an ideal beauty in her day and that “13 young men killed themselves because she rejected” them. Framed in this way, it’s unsurprising that few have expressed their doubts based on the lack of sources or citations of any kind, focusing instead on the princess’ appearance.

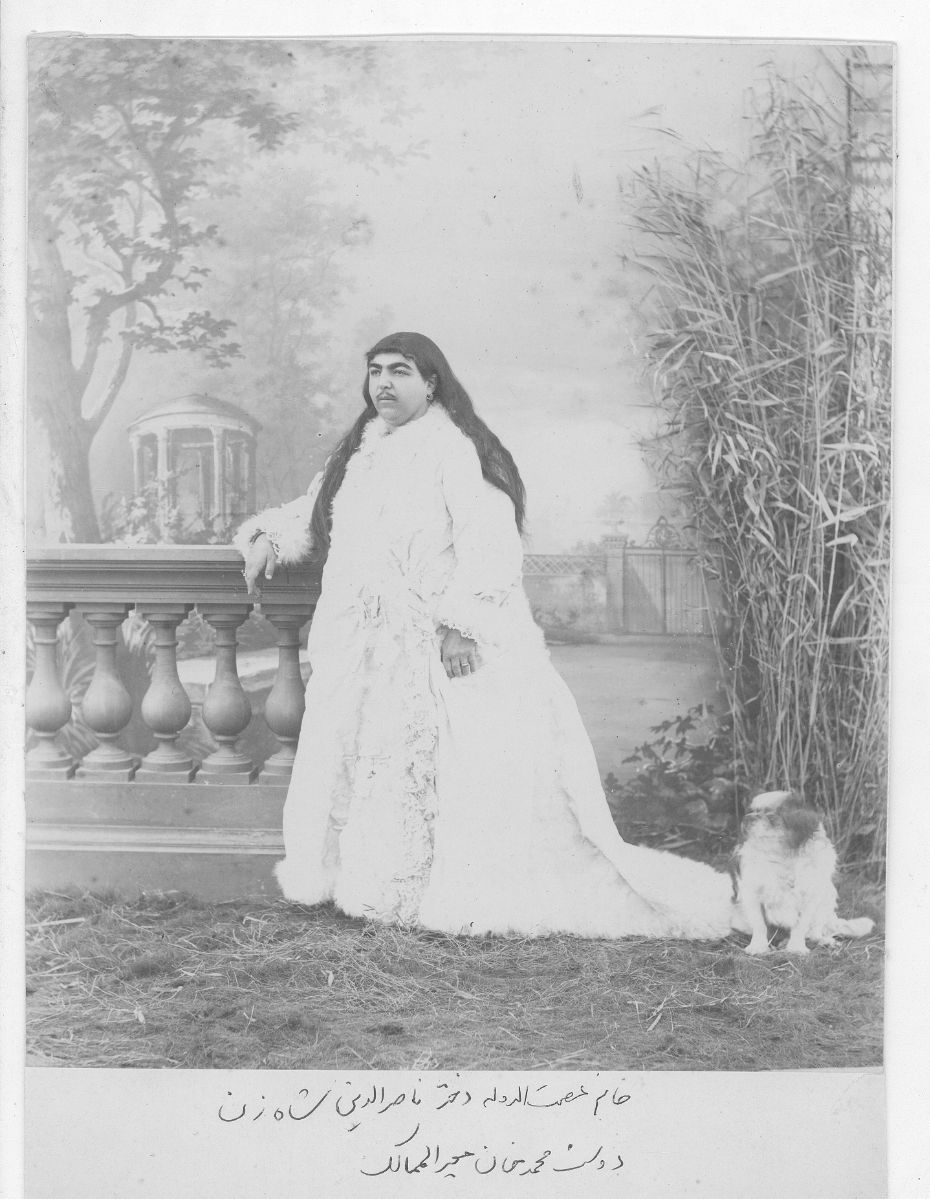

Princess Fatemeh Khanum “’Esmat al-Dowleh” (1855/6-1905). Inscribed: “Khanum ʻIsmat al-Dawlah daughter of Nasir al-Din Shah, wife of Dust Muhammad Khan Muʻayyir al-Mamlik,” and dated mid/late 19th century. Part of the collection of the Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (ع 3-5216). Courtesy Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran. This is the image that features in the junk history meme.

This is, of course, exactly the kind of reaction desired when creating a meme in the hope it will go viral. Facts and sources be damned, even if it comes from a so-called “educational/history” page. They won’t make it go viral like sensational claims that bank on internalized misogyny and blinkered concepts of beauty.

Then there’s the sad truth that few will bother to check the facts for themselves. Those who do often run up against similar misleading factoids, creating a jumble of confusing and unreliable junk history that obscures good sources and information. For instance, well-meaning individuals commenting on this meme are often quick to claim that the subject in the photo is a male actor portraying the princess. Others go further and state that not only is it an actor, but the portrayal was done to ridicule the princess, whose “real” picture they include in the comments. Neither claim is accurate.

The historical reality of this junk history meme is, like all history, complex, and deeply rooted in a period of great change in Persian history that involved issues like reform, nationalism and women’s rights. At its core, however, is a story of not one, but two, Persian princesses who both defined and defied the standards and expectations set for women of their time and place. Neither one, incidentally, was named “Princess Qajar,” though they were both princesses of the Persian Qajar dynasty.

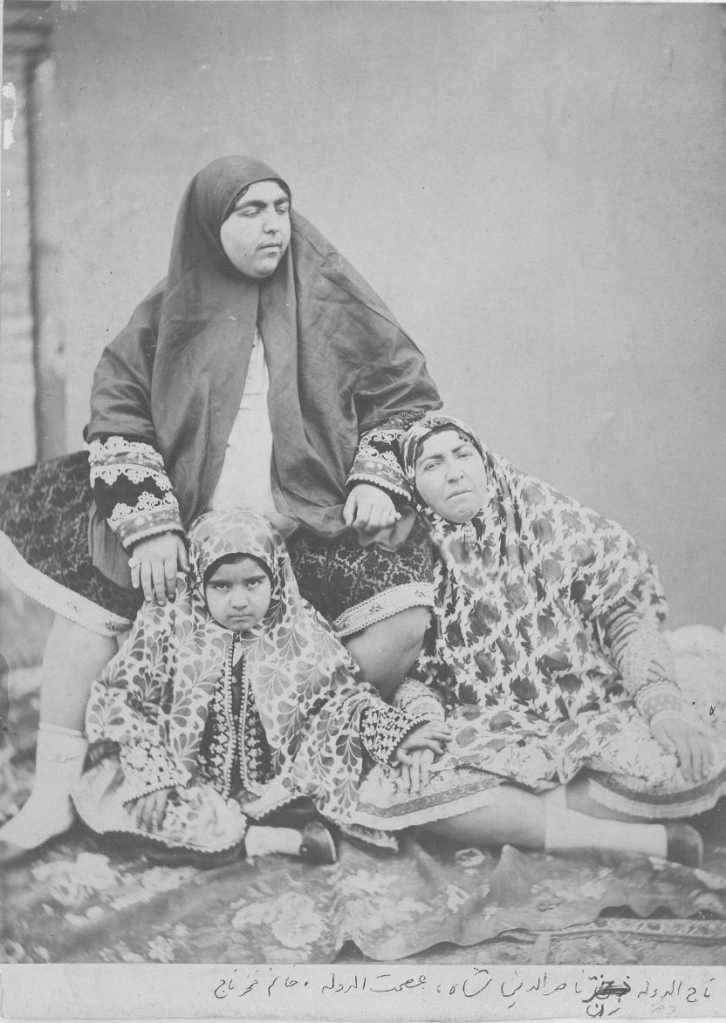

The primary figure in this history is Princess Fatemeh Khanum “‘Esmat al-Dowleh”[1] (1855/6-1905), a daughter of Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar (1831-1896), King of Persia from 1848-1896, and one of his wives, Taj al-Dowleh. The photograph circulating is indeed ‘Esmat, not an actor, and was taken by her husband circa the mid- to late-19th century. This information alone, readily available online and in print, contradicts the claim that ‘Esmat was “the ultimate symbol of beauty… in the early 1900s.” Since the photo of ‘Esmat was taken years before then, and she died in 1905, it’s a stretch to make her an icon of a period she barely graced.

The only part of the meme that has a grain of truth to it is that there was indeed a period in Persian history when ‘Esmat’s appearance – namely, her “mustache” – was considered beautiful. According to Harvard University professor Dr. Afsaneh Najmabadi, “Many Persian-language sources, as well as photographs, from the nineteenth century confirm that Qajar women sported a thin mustache, or more accurately a soft down, as a sign of beauty.”[2] But, as Dr. Najmabadi clearly points out, this concept of beauty was at its height in the 19th century. In other words, the 1800s, not the 1900s, as the meme claims.

‘Esmat, a product of her time, place and status, was no exception. In Dr. Najmabadi’s book, Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity, she relates an anecdote of a Belgian woman’s encounter with ‘Esmat at the Persian court in 1877: “In her description of ‘Ismat al-Dawlah, Serena observed that ‘over her upper lips she had soft down of a mustache which gave her a manly look.’”[3] This does not mean, however, that ‘Esmat stood out as a symbol of this type of beauty. In fact, as will be addressed, her image may have held far greater power.

Unfortunately, not only does the “Princess Qajar” meme boil down this deeply-nuanced element of cultural history into junk history clickbait, it also makes it worse by adding the sensational claim that thirteen men killed themselves over their unrequited love for her. Naturally, there is no source given to support this claim, which appears to be pulled from thin air. Were it true, it would seem like worthy material to include in even the shortest legitimate biographical information about ‘Esmat, but it doesn’t appear anywhere.

There are, however, at least two good reasons to disbelieve this claim. First, ‘Esmat was probably married when she was around nine or ten years old.[4] Second, the marriage was very likely arranged while she was living among the women of her father’s harem. It seems highly unlikely that she had the opportunity to meet any man not her relative, never mind beguile and reject thirteen suicidal lovers. Later, as a married woman in patriarchal Persia, it’s equally unlikely that she was being courted by amorous suitors.

It hardly seems necessary at this point to question the motivation of the meme’s creator in connecting such a dubious and sensational claim to this image. If it wasn’t already, it should be blindingly obvious that it has almost nothing to do with actual history, and everything to do with eliciting an overwhelming emotional response on social media. The fact that the means to the end was the exploitation of a woman’s appearance is hardly a surprise. That it is insidious and damaging, both to history in general and women’s history in particular, is beyond the shadow of a doubt.

The focus on historical women’s appearance without the benefit of context and analysis is, and always has been, a highly successful way to shift the narrative away from their accomplishments and diminish their impact on history. Whether or not ‘Esmat or any other woman was or is considered beautiful or not is of little consequence, which is why patriarchal history has focused so much on it. Starting and ending the conversation about a woman on the subject of her appearance almost guarantees that it will be all most people remember about her. In ‘Esmat’s case, keeping her anonymous by giving her the generic appellation, “Princess Qajar,” ensures that those who wish to know more will not have much to go by.

Not that the creator of the meme did any actual research to create the meme. That would have taken effort, skill, persistence, and an actual desire to preserve and perpetuate good history. Had they done so, there’s no question that the resulting meme wouldn’t have gotten the volume of response that makes a meme go viral. But it would have contained far more interesting information than what they have invented and/or distorted. They would have discovered, for instance, that ‘Esmat was one of the most photographed women at her father’s court, and it wasn’t because she conformed to contemporary ideals of beauty.

As the second daughter of Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar, ‘Esmat was trusted enough by her father that she was given the responsibility of serving as the host for female foreign guests to the court.[5] Against tradition, she learned to play the piano and became a photographer with a private studio in her home.[6] More significantly, there are instances of her using her influence with her father, such as when she convinced him to let her husband back into the country.[7] Like other royal women at her father’s court, ‘Esmat appeared to be a competent woman with a fair amount of agency.

In fact, the appearance of ‘Esmat and other women of the harem may have held a power far greater than that of merely attracting a multitude of suitors. Art historian Dr. Staci Gem Scheiwiller has argued that the large number of photographs of the women of Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar’s harem “had the ability to demonstrate a development of a female revolutionary consciousness.”[8] The sheer volume of photographs of ‘Esmat would have put her visually at the front and center of this social and cultural revolution.

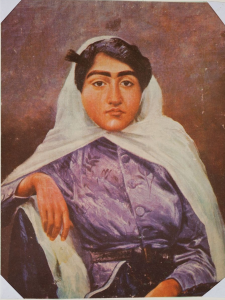

At the literal front of it was the other princess of the Qajar dynasty who has been mistakenly associated with the unfortunate meme because of the vague “Princess Qajar” reference: Princess Zahra Khanum “Taj al-Saltaneh”[9] (1884-1936). The 12th daughter of Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar, and half-sister of ‘Esmat, Taj was a feminist and a nationalist who supported a cultural and constitutional revolution in Persia.

According to Dr. Najmabadi, Taj “…articulated some of the most eloquent arguments put forward by women for unveiling as a first necessary step toward women’s participation in education, paid work, and progress of the nation.”[10] And Dr. Scheiwiller highlights a key passage from Taj’s published memoirs, Crowning Anguish: Memoirs of a Persian Princess from the Harem to Modernity 1884-1914: “When the day comes that I see my sex emancipated and my country on the path to progress, I will sacrifice myself in the battlefield of liberty, and freely shed my blood under the feet of my freedom-loving cohorts seeking their rights.”[11]

In their own time, ‘Esmat and Taj were not defined by their appearance. Their accomplishments were not the result of either setting or copying cultural standards of beauty. They were women of merit and substance whose stories deserve to be told and perpetuated in a respectful and meaningful way, not diminished and ridiculed.

In writing of the women of the Qajar court, like ‘Esmat and Taj, whose pictures hold so much historical meaning and significance, Dr. Scheiwiller poignantly wrote, “The photograph of oneself was able to transform one from being meaningless, whose story would not be told, to one of a face etched in time.”[12]

It would be a travesty to sit back and let a fatuous meme mar the true beauty and historical importance of these women and their images.

***An update of sorts on this blog post was published on August 10, 2023. See The Slow Death of the “Princess Qajar” Meme and How to (Maybe) Kill It Once and for All.***

***

Main image credits: Cropped images of (left) “Khanum ʻIsmat al-Dawlah” circa mid/late 19th century from the collection of the Institute for Iranian Contemporary Historical Studies (ع 3-5216), and (right) a “Cabinet Portrait” of Taj al-Saltaneh from the private collection of Bahram Sheikholeslami. Both images courtesy of the Harvard University online database, Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran.

[1] Sources include a variety of spellings for the Persian names. In Princess Fatemeh Khanum’s case, she is generally referred to ‘Esmat or ‘Ismat (both with and without the accent mark), and variations of her second name include ed-Dowleh and al-Dowlah.

[2] Najmabadi, Afsaneh. Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005, 233.

[3] ibid 232

[4] Her husband was ten at the time of the marriage (see Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran), and her sister, Taj al-Saltaneh married at the age of nine or ten (Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran).

[5] See Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran

[6] Scheiwiller, Staci Gem. Liminalities of Gender and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Iranian Photography: Desirous Bodies. (Routledge History of Photography). Oxford: Routledge, 2016, 69.

[7] Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran

[8] Scheiwiller 73

[9] Also spelled al-Saltanah.

[10] Najmabadi 137

[11] Quoted in: Scheiwiller, Staci Gem. Photographing the Other Half of the Nation: Gendered Politics of the Royal Albums in 19th Century Iran. “The Photograph and the Album.” ed. Jonathan Carson et al. Edinburgh: MuseumsEtc, 2013, 64.

[12] ibid 65

A junk history meme led me to this blogpost. Thank you for putting so much effort to explain.

LikeLiked by 1 person